Daniel Defoe (1660?-1731)

Daniel Defoe was born and grew up in turbulent times. On Defoe’s birth, see J. A. Downie’s essay “Defoe’s Birth,” which you can access here. We would like to thank Professor Alan Downie and The Scriblerian and the Kit-Cats for their permission to post this essay here. Defoe’s youth was marked by the plague, the great fire of London, a series of wars with the Dutch, and the persecution of Dissenters. His adult life would be equally unstable, particularly where financial matters were concerned. After receiving an education at a dissenting academy, Defoe embarked on a series of mercantile ventures, working with a number of different products, ranging from wine to bricks to hosiery. As Maximillian E. Novak has pointed out, this diversification was typical for a business man in a time of a shifting national economy (Master of Fictions 77). Defoe was also a highly active investor, investing funds in such ventures as the perfume trade and in a diving machine. At times he was highly successful, yet at other points in his life his business affairs were in disarray. Defoe experienced several bankruptcies, one in 1692 and another in 1703.

Daniel Defoe was born and grew up in turbulent times. On Defoe’s birth, see J. A. Downie’s essay “Defoe’s Birth,” which you can access here. We would like to thank Professor Alan Downie and The Scriblerian and the Kit-Cats for their permission to post this essay here. Defoe’s youth was marked by the plague, the great fire of London, a series of wars with the Dutch, and the persecution of Dissenters. His adult life would be equally unstable, particularly where financial matters were concerned. After receiving an education at a dissenting academy, Defoe embarked on a series of mercantile ventures, working with a number of different products, ranging from wine to bricks to hosiery. As Maximillian E. Novak has pointed out, this diversification was typical for a business man in a time of a shifting national economy (Master of Fictions 77). Defoe was also a highly active investor, investing funds in such ventures as the perfume trade and in a diving machine. At times he was highly successful, yet at other points in his life his business affairs were in disarray. Defoe experienced several bankruptcies, one in 1692 and another in 1703.

Although Defoe is best known now for his novels, much of his writing is related to political, social, and business issues. This is evident in his early writing. One of his first works, An Essay upon Projects (1697), was a series of proposals that touched on such topics as banking, highway maintenance, education, and insurance. Defoe also wrote about contemporary religious issues, and was charged with libel for one pamphlet that responded to a proposed bill to outlaw occasional conformity, The Shortest Way with the Dissenters (1702). Part of his punishment was to stand in the pillory, a potentially dangerous sentence as it left the prisoner vulnerable to the whims of the mob. However, Defoe’s friends turned the public punishment into an opportunity; not only did they stand around him as he stood in the device, but the occasion was used to sell his Hymn to the Pillory, a poem that ridicules the justice system, to the public.

Defoe’s concern about socio-political matters frequently intersected with his love of literature, and he began publishing poetic works that dealt with issues of public concern. His remarkable True-Born Englishman (1701), for example, is a satiric poem written to defend King William III, who had been frequently criticized for his foreign upbringing. What right, Defoe suggests in the poem, do the English people, themselves a rag-tag group of nationalities, have to criticize those who are from elsewhere? Another of his writing ventures was a newspaper, The Review, which was, as Paula R. Backscheider has recently noted, a “ground-breaking periodical that moved English journalism in new directions” (Online DNB).

For a significant period of his life, Defoe worked as a political agent and a propagandist. Indeed, he was a spy for Robert Harley, Chancellor of the Exchequer, in the year leading up to the Anglo-Scottish union. This involved visiting Edinburgh and Glasgow, writing to Harley to keep him in touch with Scottish sentiments on the union, and producing a number of essays and pamphlets promoting the cross-border alliance. After the union took place in 1707, Defoe continued as a political writer, working, at different times, for both Whig and Tory administrations.

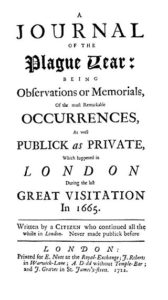

As Defoe wrote the works that we are most familiar with now—Robinson Crusoe (1719), Captain Singleton (1720), Moll Flanders (1722), Colonel Jack (1722), Journal of the Plague Year (1722), and Roxana (1724)—he was also producing numerous innovative texts in widely varied genres and on very different themes. For example, alongside the significant number of political pamphlets and essays produced, he published travel literature, such as The Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-6), commentaries on religion, such as the satirical Political History of the Devil (1726), and self-help manuals, like The Family Instructor (1715).

Defoe scholarship has been vibrant and exciting for many decades, but there is much left to do. Backscheider has recently reminded us that less than a quarter of Defoe’s works are currently in print, a dilemma that scholars are currently working to resolve. And there are continually exciting new avenues opening up through which we can approach Defoe’s corpus. It is the objective of this society to find creative new ways to facilitate this scholarship and to open new avenues of collaboration.

This entry has only briefly touched on a few key facts about Daniel Defoe. There are numerous superb scholarly biographies on Defoe and his work that will allow you to explore at greater length his life, and the impressive variety of his work, both in terms of subject matter and genre. You might start with some of the following, to which I am indebted for this brief biography. They are listed in order of the date of publication, starting with the most recent:

- P. N. Furbank and W. R. Owens. A Political Biography of Daniel Defoe. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2006.

- John Richetti. Life of Daniel Defoe: A Critical Biography. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2005.

- Maximillian E. Novak. Daniel Defoe: Master of Fictions: His Life and Ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Backscheider, Paula R. Daniel Defoe: His Life. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

For those with access to the online Oxford Dictionary of Biography, you might also want to check out its excellent, brief biography of Defoe, contributed by Paula R. Backscheider.